contact: thistlepixie@gmail.com

Kristin Brenneman Eno

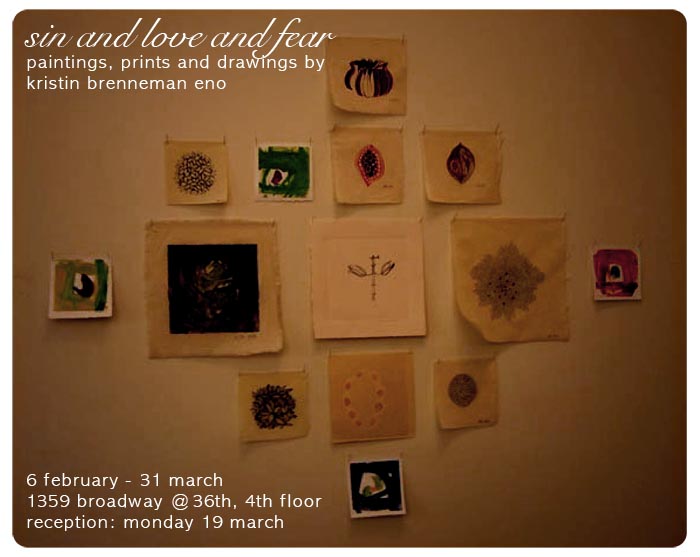

Sin and Love and Fear

by Maria Fee, Curator

Genesis 1 relates how God set in motion the earth’s regenerative character. Kristin Brenneman Eno’s imagery summons the idea of God’s call to be fruitful and multiply. Her organic shapes grow and move—they are hardly ever static. Seed and pod-like characters hint at the potential of what is to be, they obey God’s command.

In Kristin’s world the physical properties of plant forms also evoke our inner being: vines can become veins, seeds are cells, flowers become organs. On her canvases our inner world comes to life like Genesis’ flourishing narrative. The fibrous, tissue-like imagery locate us close to the heart of our life with God, others, and ourselves.

The layered, processed-oriented paintings speak of a world where physical realities teach us of our inner spiritual workings. They are the incarnation of our interior moaning and groaning, the wrestling with sin, love and fear that “grow” and bind us closer to God.

Exhibition continues through March 2007 during office hours (by appointment, contact arts@redeemer.com) or during evening and weekend events.

For information on purchasing artwork, contact arts@redeemer.com.Regarding Faulkner

by Kristin Brenneman Eno

“The aim of every artist is to arrest motion, which is life, by artificial means and hold it fixed so that a hundred years later, when a stranger looks at it, it moves again since it is life.” William Faulkner

William Faulkner put words to the indescribable events and images that make this life real and strange and heart-wrenching and beautiful. I am constantly awed by his words, so I decided a few years back to use them in the titles of my paintings, which I have no words for, but know that if anyone could put words to them, it would be Faulkner. He knows how to evoke the emotions deep within the human heart: wonder, doubt, fear, love and longing. His words brilliantly give voice to the complexity of thought and experience. He reminds us that everything, from love to faith to death, is beautiful and ugly all at once, and that thought cannot be contained in the language that we use. His words peel back life, showing us the core. I can only hope to do some such thing with my paintings. These paintings may seem far removed from Faulkner’s world, in that they do not depict rural Mississippi life in the early 20th century. But I feel my paintings connecting to his writing when they depict the inexplicable, the shrouded, the almost there.

The title of this exhibition, Sin and Love and Fear, comes from Addie Bundren’s words in As I Lay Dying, and also references three of the most powerful human drives. Addie’s narration from beyond life (she is dead when she speaks) moves me to reflect on my own life and the words that come and go through it:

I would think how words go straight up in a thin line, quick and harmless, and how terribly doing goes along the earth, clinging to it, so that after a while the two lines are too far apart for the same person to straddle from one to the other; and that sin and love and fear are just sounds that people who never sinned nor loved nor feared have for what they never had and cannot have until they forget the words (As I Lay Dying, Addie, pp. 173-4).

Certainly language and its use as communication is a miracle, but sometimes I rely too readily on it: I often wish I could “forget the words.” Whenever I follow Addie’s longing to strip words away, I am left with two things: the visual world, and thoughts that transcend language. I respect what images have to teach, but so often I won’t give them the time. Faulkner reminds me that even while he carefully chose his words (just as I choose words to speak and write, to connect with the world around me), he found a way to transcend those very words and to come out on the other side, in the seething heart of life, with all its tragedy and despair and wonderful love and beauty. In that sense, his art helps me to see this life more deeply. He somehow arrived at the point where, amazingly, he could use the medium of language to evoke and invoke that which is beyond it. I can only hope to do the same with the images that I make.

Most of the titles of the paintings in this show reference passages from As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury:

As I Lay Dying (1930)(The book is divided into sections, each with the title of the name of the person speaking. These names are given in the reference at the end of each quote.)

. . .as if the road too had been soaked free of earth and floated upward, to leave in its spectral tracing a monument to a still more profound desolation than this above which we now sit, talking quietly of old security and old trivial things (Darl, p. 143).

He did not know that he was dead, then. . . I would think about his name until after a while I could see the word as a shape, a vessel, and I would watch him liquefy and flow into it . . . (Addie, p. 173).

. . . how terribly doing does along the earth, clinging to it, so that after a while the two lines are too far apart for the same person to straddle from one to the other; and that sin and love and fear are just sounds that people who never sinned nor loved nor feared have for what they never had and cannot have until they forget the words (Addie, pp. 173-174).

--the wild blood boiled away and the sound of it ceased. Then there was only the milk, warm and calm, and I lying calm in the slow silence, getting ready to clean my house (Addie, p. 176).

The Sound and the Fury (1929)(The book is divided into sections according to the date on which they were written, each by a different character. The book section and name of narrator is given in the reference at the end of each passage.)

I could hear us all, and the darkness, and something I could smell. And then I could see the windows, where the trees were buzzing. Then the dark began to go in smooth, bright shapes, like it always does (April 7, 1928; Benjy).

The street lamps would go down the hill then rise toward town I walked upon the belly of my shadow. I could extend my hand beyond it (June 2, 1910; Quentin).

I could see a smoke stack. I turned my back to it, tramping my shadow into the dust (June 2, 1910; Quentin).